Currently reading

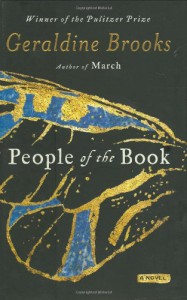

People of the Book

***Note: this review assumes that you've read the book.***

One-sentence summary: The contemporary thread of People of the Book was disappointingly melodramatic, and the historical threads had too little depth and feeling for the periods and the personalities.

People of the Book tells a fictionalized account of the hidden history of the Sarajevo Haggadah, a book that is known to have survived wars, cross-country journeys, years in hiding, and undoubtedly multiple owners.

Real history. A Haggadah is a book of readings for the Jewish seder service. The Sarajevo Haggadah, a real book, appears to have been made in Spain in the mid-fourteenth century, as a wedding gift. What we know of its history is only several lines long: the National Museum of Sarajevo purchased it from a man by the name of Josef Kohen in 1888; a note in it says that it changed hands in 1492 when Jews were expelled from Spain; an inscription from 1609 says it passed the Catholic Church's inspection by a (presumably generous) priest, saving it from being burned as a heretical book; it made a trip to Vienna for several years (to be studied) before being returned to Sarajevo; in 1941 the Nazi regime specifically searched for it in the Museum, but it was hidden from them by the director and the curator of the museum (the curator also saved a Jewish girl); during the Bosnian War in the 1990s the book was saved again from bombings by the director of the museum and put in a bank vault until the end of the conflict.

Synopsis. The contemporary segments tell the story of Hannah Heath, a book conservator who has been hired to stabilize the Haggadah before it is put on display at the encouragement of the U.N. as a testament to unity and peace. The Haggadah is a particularly intriguing book because it is illuminated with detailed, representational illustrations--something that Jewish manuscripts of the time did not have. Hannah finds artifacts in the pages of the book that present mysteries and may lead to a better understanding of where the book has been: a tiny butterfly wing, a white hair that is dyed with saffron, a wine stain, a stain that appears to be made of salt water. These artifacts each of course have a story critically linking them with the creation and journey of the Haggadah--and the reader has the benefit of seeing the stories in full, but Hannah does not (she guesses only at the edges of them). The historical segments move back in time from World War II to the creation of the illuminated illustrations by a black female Muslim artist in 1350. (There is a black woman at the seder table in one of the illustrations, and Ms. Brooks takes the liberty of fictionalizing her as the artist.)

Actually, you know what? I won't go into the gory details of the synopsis because Cate Ross has done it better than I ever could right here.

I also like her snarky take on the whole book:

....This book is terribly cold. Family members shun each other, religious calling is nothing more than a sanctuary from murder or the shame of being born Jewish. The Jewish families that possess the Haggadah never use it for seder; they are too busy being murdered apparently. It's a fairly cynical novel--the Haggadah is never loved, never treasured as a family relic, never shown except as the byproduct of melodrama. It's as though Brooks has only a theoretical understanding of what a Haggadah means, and she has a blood-thirsty imagination that can't be set to the quieter themes.

Like Cate, I would have loved to have seen what this Haggadah meant to a real family while it was in use, rather than the relentless destruction, rape and oppression that we see associated with it in a peculiarly superficial fashion. And in fact, the actual Sarajevo Haggadah shows lots of evidence of use, presumably by many, many families (more than one wine stain, for instance). The book should feel not just momentous to us, it should feel magical and loved.

The historical sections. The historical stories all occur at critical moments in the Haggadah's journey, and thus are dramatic, but (oddly) they have very little feeling to them. For instance, the longing for freedom of the black slave artist somehow rings hollow. How is that even possible, with such a weighty, moving subject as slavery? All I can think is that the addition of the lesbian relationship and forced parting, and the perfunctory rape by her previous master, and her exceptional circumstances as a Muslim artist trained in a Christian illuminated style, all make the narrative of her short story too packed, in such a small space, for us to feel her plight in our cores. Sometimes simplicity is the more powerful way of telling the story.

Dropped threads. The short forays into these overly-meaningful moments in the Haggadah's history also do themselves a disservice by inevitably dropping threads. For example, Ruti steals her gentile infant nephew from a cave after her sister-in-law has given birth to what she thinks is a stillborn baby, and we hear nothing of what happens to the mother, or the father, who is being tortured by the Inquisition in the "place of relaxation," or in fact of the baby himself. Thus, in terms of plot, the baby is only there to provide the salt-water stain on the book when he's submerged in the sea by Ruti in a ritual to make him Jewish, yet we end up wondering what happened to him. It's hard to feel emotionally attached to the historical sections when they're so clearly there to wham us over the head with "drama" and "history" without allowing us the time to care for the characters.

Dull contemporary melodrama. Hannah's story was by far the least interesting part of the novel, yet it's what theoretically ties it all together. The Hannah thread feels self-absorbed and almost juvenile compared with the historical sections, even though it's fleshed out more. And even in this story line, Ms. Brooks can't resist melodrama: Hannah's mother, an accomplished neurosurgeon, was not only "too absorbed in her career" to be a good parent, but essentially killed Hannah's artist father, presuming for him that he wouldn't want to live without eyesight; Hannah's lover has not only lost his wife in the Bosnian war, but his son has suffered a traumatic injury and is brain-dead in the hospital.

In sum. I've been on the hunt for great historical fiction since reading Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, but I'm starting to wonder whether popular historical fiction is often just fluffy contemporary literature in disguise. So much of historical fiction inserts fantasy, or chick-lit, or tells the story from the point of view of invented historical characters observing real historical figures. Someone, please bring on the real stuff.

3

3

1

1